Many of us reap the rewards of native mason bees pollinating our fruit trees in the spring. We provide houses to attract and keep these beautiful bees close to our gardens. In return, our duty to the bees is to clean the houses at the end of the season, to prevent parasites from reproducing; and to put away healthy cocoons to be released next year, to support a robust mason bee population.

The truth is in nature, mason bees do not live together in such dense communities. Instead, they nest in smaller groups in several different places – crevices in trees, old beetle holes, cedar shake roofing – to reduce vulnerability to many different parasites. These include parasitic wasps, Houdini flies, mites, earwigs, and woodpeckers, who are attracted to the carbohydrate and protein-rich pollen loaves made by female bees to feed their young. In addition, birds and bears seek out mason-bee larvae.

Who are these parasites?

Hairy fingered mites

Hairy fingered mites are typically the most common mason-bee parasites. Looking like a pile of yellow-orange specks, they often take up the whole nesting cell and consume all within. Mites enter the nesting cells by hitching a ride on a female bee, who then lays her eggs. The mites fall off and consume the pollen loaf and bee egg. In the spring, the mites leave by hitching onto the emerging bees, and spread to the outside world.

To remove mites from the outside of the cocoons, it often takes a sand bath – a form of sandblasting if you will – which is done in the cleaning process. You can see the mites on the cocoons with a magnifying glass, or good eyesight!

Houdini flies

Houdini flies sneakily hang out at the entrance of the bee house and wait for a female to enter the nest and provision it. When the bee leaves, the Houdini fly whips in and quickly lays its eggs in the nest and leaves. When the young flies emerge, they consume the pollen loaf, thus starving and killing the mason bee egg or larva.

Parasitic wasps

If you have used paper tubes in your mason-bee house, and find a hole in the side of the tube, it has been parasitized by a parasitic wasp, who drilled through the paper to lay its eggs, usually in the mason bee larva.

Earwigs

The only sign that earwigs have been in the bee house is their poop. Small black specks are all that’s left of what was a mason bee provision loaf and egg. It’s tricky to prevent earwigs from entering the nest; mounting the house on a pole that has been covered in a sticky barrier (such as Protek Trunk Insect Barrier) is the most effective way to prevent earwigs from reaching the nest.

Woodpeckers

There is not much you can do if woodpeckers get into your bee nest; they tend to eat all the larvae, and often damage the house by chipping away at the entrance or even drilling through the side! The best way to prevent woodpeckers is by putting a wide metal mesh over the front of the house, which allows bees in but stops woodpeckers from getting their beaks far into the house.

Parasite Protection

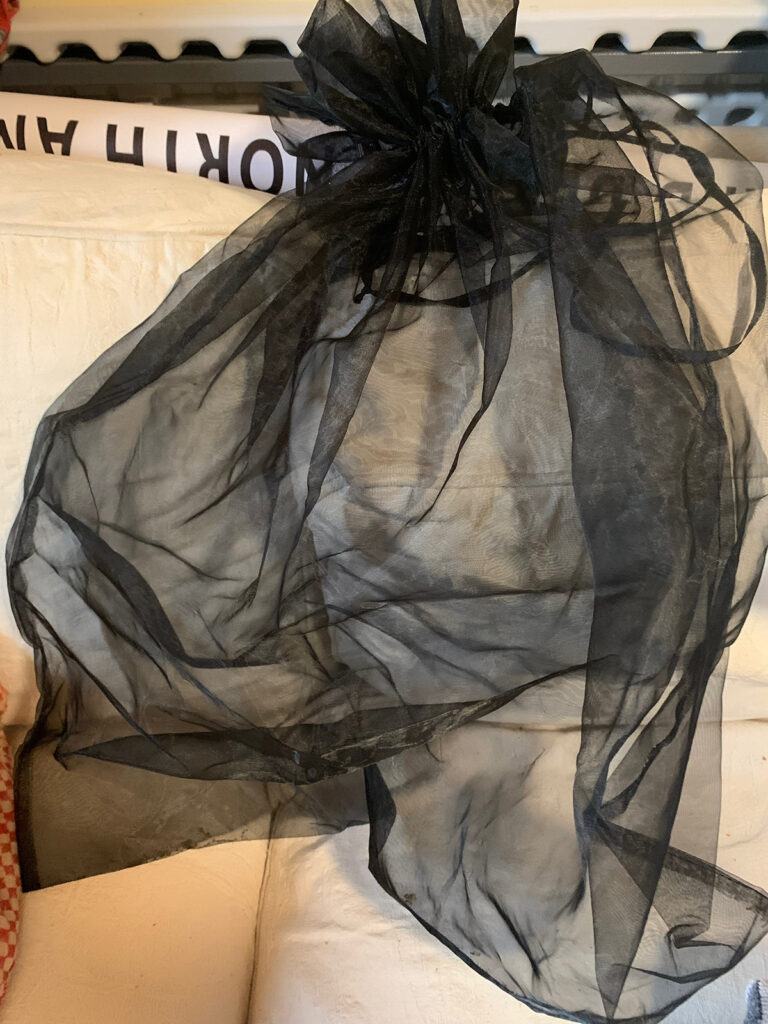

Provide extra protection by removing parasite access to your bee house for a few months every year. Take down your mason bee house at the end of June, place it in a fine cloth/muslin bag and put it in your garage until October/November when you can harvest the cocoons and clean it. Flies or wasps will try to escape from the bag and re-infect another mason bee nests, so keep an eye on the bag and kill any that emerge.

Conclusion

If you’re wondering if having a mason bee house is worth the hassle, it’s a good question; you need to offer two hours per year to care for them in return for higher fruit and vegetable yields in your garden.

Leave a Reply